Puebla, Mexico – Talavera ceramics to mole poblano

Inside the brilliantly hued Talavera-tiled kitchen, I was learning a seriously important “don’t” of poblano cuisine.

Don’t inhale.

At least not while leaning above chiles roasting over a stove’s open flame. It’s not as painful as rubbing chile oil in your eyes, but spicy steam will fill your lungs. The resulting coughing fit, however, was a small price to pay for learning how to make Mexico’s national dish, mole poblano, in the city where it was born.

In Puebla, often considered the gastronomic capital of Mexico, the domain of the kitchen has a history all its own.

Much as Guadalajara is the hometown of Tequila, mariachi and the charro, Puebla is packed with history and items that are recognized worldwide as “classically Mexican” – from mole poblano and chiles en nogada to Talavera ceramics and Cinco de Mayo.

Puebla bustles but isn’t overrun with tourists, despite the national treasures and traditions started here that tend to attract more Mexican travelers. Because most of the city’s historical features are focused in the Centro Histórico, the original heart of Puebla retains the feeling of a small, colonial town.

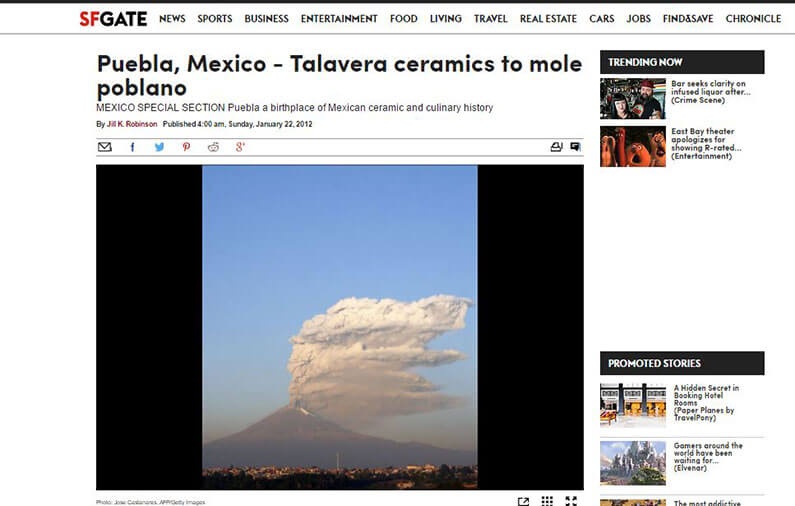

Established in 1531 along the main route between Mexico City and the port of Veracruz, Puebla is ringed by volcanoes and snowy peaks, and lies at the foot of Popocatépetl, one of Mexico’s most active volcanoes. After nearly 50 years of dormancy, the glacier-clad volcano (whose name combines the Nahuatl words for “smoking mountain”) came back to life in 1994 and now regularly spews smoke and ashes. (“Popo’s” largest major eruption was in December 2000, when lava flowed for weeks.)

Walking through the Centro Histórico, it’s difficult to not be distracted by the Crayola-colored buildings, mouthwatering smells from sidewalk restaurants and ceramic tiles that glint in the sun. The center of Puebla, the Plaza de Armas (the zócalo), is lined with shade trees and dotted with benches, attracts everyone from tourist to clown to musician. On one side of the zócalo is Puebla’s neck-craning cathedral, which has the tallest church towers in Mexico.

The cathedral is one of more than 60 churches and former convents in town.

At the top of the list, the gilded Rosario Chapel in the Church of Santo Domingo is sometimes described as the eighth wonder of the world for its elaborate plaster and gold leaf decor. Looking at its intricate details above me, it seemed as if it could be spun from sugar – not entirely far-fetched in this town – and would give me cavities if I stared too long.

Cinco de Mayo

During my visit, preparations were under way throughout town for one of the largest festivals of the year. Colorful decorations dripped from buildings, lampposts and store windows. Parade-viewing stands neared completion. Families relaxed in the city’s plazas, while kids splashed in fountains.

Oddly, one of the major sources of pride in this city also happens to be Mexico’s least understood holiday.

Cinco de Mayo is often mislabeled as Mexico’s Independence Day (mostly by U.S. distributors of Tequila and margarita mix). The date instead marks the May 5, 1862, defeat of the French army at Puebla.

Marching from Veracruz to Mexico City, the well-outfitted French army encountered a much smaller Mexican militia – and was soundly defeated. (The Mexican victory was short-lived; a year later, France invaded again and ruled the country for three years.)

Predictably, the largest Cinco de Mayo celebration in Mexico is here in Puebla. The biggest event of the day is a full-blown military parade that lasts for hours and winds through the city.

Never far from the celebrations were the thousands of food stands selling festival treats, including poblano favorites – being prepared by people who know not to inhale the vapors.

Comida poblano

According to legend, the people responsible for the region’s most sinfully delicious dishes and desserts were Puebla’s nuns.

Mole poblano, a rich blend of chiles, spices, chocolate and nuts served over turkey or chicken, was made the first time by the nuns of the Convent of Santa Rosa in honor of a visit by the archbishop. The old kitchen of the convent, covered in Talavera tiles, is still open to visitors.

The word mole comes from the Nahuatl word for sauce, but it describes a number of sauces and dishes used in Mexican cooking. The best known of these, mole poblano, is named for its origin in Puebla. However, it seemed as though pipián, a green mole that includes hulled pumpkin seeds (pepitas), is featured on menus as frequently as mole poblano.

Nuns at the Convent of Santa Monica are said to have originated chiles en nogada for Agustín Iturbide, the first ruler of independent Mexico. The patriotic dish is served in and around the month of September to celebrate Mexico’s independence from Spain. Poblano chiles stuffed with ground meat, nuts and fruit are topped with a walnut cream sauce and garnished with pomegranate seeds to represent the green, white and red colors of the country’s flag.

Not to be outdone, the nuns of the Convent of Santa Clara were known for sweets, including jamoncillo (a mix of pumpkin seeds, sugar and sometimes almonds), camote (crystallized sweet-potato candy with fruit flavors) and the tortita of Santa Clara (a cookie topped with pumpkin-seed cream). The treats are still available on the two-block stretch of 6 Oriente referred to as Calle de los Dulces (street of sweets), near the building that once housed the convent.

Cooking classes

I found the only thing better than trying Puebla’s food is taking a cooking class here.

My class with Chef Alonso Hernández at the Mesón Sacristía de la Compañía was three hours, but in that short stretch of time, I learned the secrets behind both red and green sauces, mole poblano and chalupas (another Puebla favorite).

The classes take place in the hotel’s Talavera kitchen (where I learned the first poblano cuisine “don’t”).

The best part of the class: Eating everything I prepared – served on Talavera platters that matched the colors of the kitchen’s stove.

Talavera treasures

It’s hard to miss Talavera in Puebla. The brightly colored tiles (azulejos) cover the walls of Baroque buildings and entire kitchens, meals in restaurants are delivered atop the glazed ceramic plates, and urns and bowls line the windows of shops in the Centro Histórico. The city is the largest producer of this type of ceramics in the world, and is often referred to as the City of Tiles.

The technique itself was brought to Puebla by Spaniards from the region of Talavera de la Reina. The majolica-type earthenware was decorated originally with blue adornments on a white background, but Mexican craftsmen blended the borrowed process with their own interpretation, local clays and natural pigments. Colors in Talavera design today can include green, yellow, black and orange with the original blue.

Production of Talavera is as old as the city itself. Although Talavera ceramic is made in several other areas of Mexico, the official Talavera can only be produced in Puebla and nearby communities because the Mexican government has designated and protected the Talavera produced in certain workshops in Puebla. These manufacturers are required to follow a strict fabrication process and use only clay from a few approved sites.

Uriarte Talavera, the largest producer of Talavera in Latin America, has been making the ceramics since 1824. During the tour, I followed the process from start to finish – molding pieces on potters’ wheels, firing in kilns at 1,560 degrees, glazing, painting and firing one final time.

After the first firing, Talavera is tested to make sure it hasn’t cracked. A guide handed me a terra-cotta-colored cup and a metal stick. A soft smack on the side produced a ringing tone. If it were cracked, the cup would have a hollow sound.

After the tour, I fingered the ceramic samples in the factory’s shop. It makes sense that in this place, the dishes (cuisine) and the dishes (ceramic) would grow up together.

Somewhere in that store were the plates I needed. With my newly acquired Puebla kitchen skills, I was eager to try my mole poblano recipe at home – without, of course, choking on chile steam.

If you go

Getting There

The Hermanos Serdán International Airport (PBC) serves Puebla. It’s also possible to arrive at Benito Juárez International Airport (MEX) in Mexico City, and take the Estrella Roja first-class bus to Puebla ($25 round-trip), which takes about two hours.

Where to Stay

Mesón Sacristía de la Compañía, 6 Sur 304 Callejón de los Sapos, Centro Histórico; 52 (222) 232-4513; www.mesones-sacristia.com. Eight-room boutique hotel on Callejón de los Sapos, which is full of antique shops. Rates start at $160 per night.

La Purificadora, Callejón de la 10 Norte 802, Paseo San Francisco; 52 (222) 309-1920; www.lapurificadora.com. Former water purification plant has grand spaces and a glass-walled swimming pool. Rates start at $205 per night.

Where to Eat

Restaurant la Compañía, 6 Sur 304 Callejón de los Sapos, Centro Histórico; 52 (222) 232-4513; www.mesones-sacristia.com. Dine on traditional cuisine of Puebla in the courtyard of the hotel. Entrees, $7 to $11.

Fonda de Santa Clara, 3 Poniente 307, Centro Histórico; 52 (222) 242-2659; www.fondadesantaclara.com. Cozy restaurant near the zócalo specializes in traditional food of the region. Entrees, $5 to $12.

La Purificadora Restaurant, Callejón de la 10 Norte 802, Paseo San Francisco; 52 (222) 309-1920;www.lapurificadora.com. Mexican fusion cuisine, served in an open-air dining room with communal tables. Entrees, $9 to $19.

What to do

Uriarte Talavera offers daily (weekday) tours of its factory. 4 Poniente 911, Centro Histórico; 52 (222) 232-1598;www.uriartetalavera.com.mx. $3.65 per person.

The Mesón Sacristía de la Compañía offers cooking classes in traditional cuisine of Puebla. 6 Sur 304 Callejón de los Sapos, Centro Histórico; 52 (222) 232-4513; www.mesones-sacristia.com. Classes: three hours $85 per person, $155 USD per couple; weeklong (15 hours) $1,500 per couple.

Museo Amparo, 2 Sur 708, Centro Histórico; 52 (222) 229-3850, www.museoamparo.com. Large collection of pre-Columbian and colonial Mexican art.

Calle de los Dulces, 6 Oriente, between Avenida 5 de Mayo and 4 Norte. Shops selling treats, some created by the nuns of the Convent of Santa Clara.

More Information

Mexico Tourism Board, (212) 308-2110; www.visitmexico.com.

Jill K. Robinson is a frequent contributor to Travel. E-mail comments to travel@sfchronicle.com.

See original source HERE